Not all the flowers I’ve been showing (and others I haven't yet) do I fully understand the mechanisms of. For most I have at least a vague sense of how they work, but some are surprising even to me. That is: while looking in certain obvious directions and playing with various forms I’ve across a few that behave as wanted—they open and close reliably and in interesting ways just by pulling and pushing at two points. That doesn’t mean I necessarily know what’s going on.

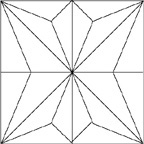

Of the three principles I mentioned in an earlier post—preliminary fold, Miura and twist—the Miura has perhaps been studied most by physicists and engineers, its pattern having been invented after all by a physicist who wanted a nice reliable way of unfurling and refurling satellite panels in space. Even with this pattern, it seems to me, there is room for further research, and studying pop-up applications is a great way to do it. I’ve echoed the Miura pattern symmetrically across one axis, to take the shape of a leaf or a flower; it folds up just as nicely as the unreflected pattern. How many more axes can this be done for? More to the point: the Miura pattern can be made VERY irregularly, and it will still fold up—in one unvarying sequence, and ending up flat; but pulled or pushed, it will go through an interesting succession of phases before it reaches the end state. (Unlike the regular pattern, which is a smoother and more simultaneous, hence for me a more boring process.) What guides the expansion or collapsing sequence with these irregular Miuras, and their sudden bursts? How much irregularity will be tolerated before the succession breaks down? What happens with radial forms of Miura? And so on. The beauty of origami is that you can test these questions out almost as soon as you’ve thought of them. And if you’re a tenured university professor someplace, you can even write a paper & get a nice grant for doing just that.

At the right level of abstraction, the Miura map fold serves a paradigm for what one looks for in an origami pop-up. --How does it work? A two dimensional sheet with numerous fold-lines usually has lots of options for folding back up when pressed at two sides or points. Some of these options lead to misfolds, as every tourist knows who has had the frustration of trying to close up a normal paper map. What the Miura map fold does is force the two-dimensional sheet to collapse first in one dimension, then in the other. It reduces a 2D problem to two 1D problems, and solves each in turn. You end up with ONE succession of folds, with a single choice at every one of its junctures. –What other fold sequences are like that?

These problems have a math & physics aspect that is not too closely bound to the specific mechanical properties of paper. Solutions would work just as well for a computer simulation, for hinged plywood sheets and indeed, for satellite panels. But some possibilities for pop-ups probably do rely on paper’s properties to some extent. Everyone who has done any significant amount of origami knows that paper has a memory. For almost any model, it is much easier to fold the shape after it has been unfolded back to the flat, than to fold the thing from scratch. I’m not making just the obvious point that existing creases make the folding easier: Rather, of two fold lines on the flattened sheet (say, both of them mountain folds), one made earlier in the fold sequence and one later, slight pressure on the sheet will tend to make the earlier line fold up sooner than the later one—much of the time though by no means always. The paper often has a partial preference for folding itself back up the right way, so that it takes only a little guidance or coaxing to make sure it doesn’t head into misfolds. --Why is this? And as a practical matter: could one design a model or pattern with an eye to just this effect? So that with the minimum amount of guidance, the model would fold itself back up entirely the right way? And using principles that have nothing to do with Miura folds? --It seems to me this too is a feature that a proper investigation of ‘pop-up’ origami might reveal.

Bestowers of research grants, lurking wherever you might, take note.