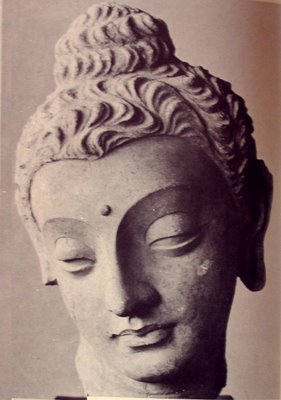

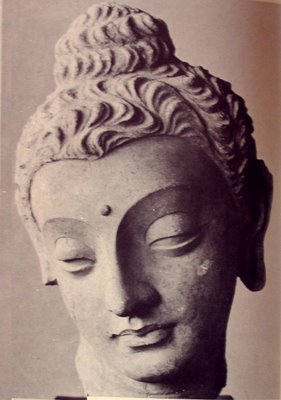

This was the image that stopped me dead in my tracks, about two years ago.

It is a stone Buddha, from the 3rd century, made in North India: artist unknown. I don’t remember anywhere having seen such repose, or balance, in a sculpture or a living face; this degree of simultaneous

worldliness and

withdrawal-from-the-world. (To meet it, be its equal: not to resign from it!). Actually I know nothing of Buddhism, and intend not to learn. But this one head—well it ranks in my book as one of the world’s great sculptures, of which there are very, very few.

Since, at the time, I was beginning to explore methods of making faces in paper, needless to say I tried to copy this head. And needless to say I failed. But the effort did spawn a series of ‘Buddha-like’ origami heads, in which something ancient and Eastern came out, maybe by way of minimalism, simplicity, modesty and humor; and maybe by using properties of paper not available to those who work in stone (a warmth, vulnerability, fragility). Here are two of the things I have in mind from then:

Now emotion, expression, are the most important things in whatever one sees, and the most obvious. But it’s no secret that origami combines its ‘art’ with its ‘science’, its expression with its intellection, more or more manifestly than any visual art I can think of. That’s one reason I’m drawn to it. Without making too much of this, origami, though it’s mostly an addiction, is also a world-view: it has its ‘Zen’. It calls forth and then pits the various human skills against each other: like a boxing match, where half the thrill is wondering which quality will win out, brute force and rage against careful training and intellect; ‘heart’ or stamina against spikes in power; an ability to take punishment against the ability to inflict it. So in origami, there is clearly technical control, engineering skill, representational accuracy, the kind of mastery that can squeeze a flap from any bit of real estate; but these are pitted against the artistic virtues: simplicity, heart, elegance, rhythm, economy, expression. Which will prevail? The contest is not less suspenseful for the square sheet of paper than it is in the square arena of the boxing ring.

Since there is technique and ‘science’ in our worldview, let us look again at that stone Buddha from the 3d century. What can be learned from it about folding technique—specifically, now, about folding curves in paper?

Look closely: you’ll see that all the lines in this sculpture are curved. But more than this: none of the curves intersect! You’ll either see

ovals, that is, lines that are continuous and endless, or curves that end by meeting other curves—but at a

tangent, at an angle of zero, so that these lines too are continuous. Where curves terminate altogether they die out softly into the plane.

Astonishing, no?

It is clear that the artist has gone out of his way to get this result. I’m no expert on Eastern sculpture, so I don’t know if this was an innovation achieved first in this particular work or if it is part of a wider trend; but there is no doubt that the technique contributes to this sculpture’s sense of repose. And no doubt, either, that it is giving a visual expression to essentially religious ideas about the flow of life, concord rather than discord, continuity, eternity etc.

For paperfolding--why does this matter?

A question that keeps coming up from various quarters, is Whether anything you do with a curved line can’t be done roughly comparably with a straight line (or straight segments). For instance: If your pattern uses a sine curve, couldn’t you just as well have used a zig-zag? Are curved folds special in any way?

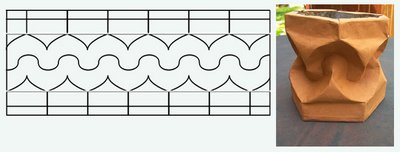

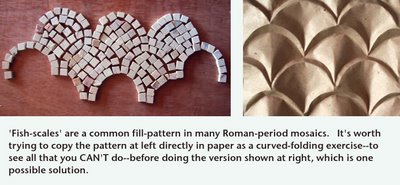

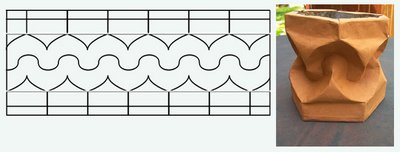

Here is a crease-pattern for the famous Huffman Tower, and a folded version. Could all the curved folds and curving surfaces here have been replaced by straight lines and flat planes? (Try it and see.)

This question about straights and curves comes up in part because some of our more technically or computationally-minded origami people seem to regard curved folds or surfaces as essentially bi-products of straight-line folds (instead of what would seem the more natural view—to consider straight lines and flat surfaces as curves with a few extra properties). One wonders, accordingly, whether this is just a fixation on the part of these designers or whether there is any basis to their approach.

The question also comes up because there are all sorts of claims in the air nowadays about the specialness of certain curved folds or their effects; for instance, about locks that are only possible with curved folds, models ‘held in tension’ by them, special surface topologies induced by them, etc. Some of these claims are true and others false; but many, it seems to me, are simply untested. Having straight-line analogs gives a means of testing in a given case whether it’s really the curvature that’s doing the work, and that’s an important reality check.

Anyway—to return to the inspiration from the Buddha—there’s at least one thing you can do with curves that you can’t do with straight-line segments: get two of them to meet at a tangent. A straight-segment’s tangent is itself; the points at its termini have no tangent. Curves, on the other hand, have no problem meeting either straights or other curves at a tangent. This is actually quite significant if you are folding surfaces containing

open folds (folds resulting in surfaces that do not lay on each other).

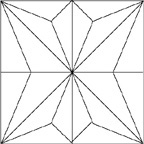

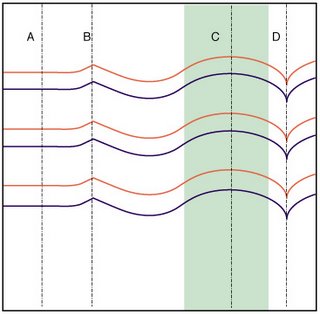

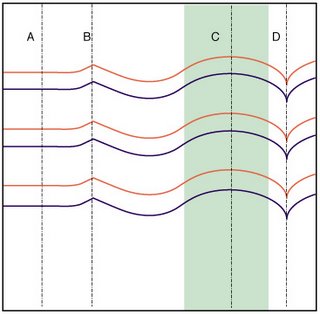

In the drawing shown here (a CP of open-folds and curves), after you’ve made the more ‘horizontal’ open folds and thus have condensed the vertical direction somewhat, you are not free to fold the surface along [A] without making a real mess--lots of new folds in awkward and unpredictable places. (This is the corrugation effect.) However, since all the horizontal lines in this region are straight, you can turn them into fully closed folds—and

then line [A] can be folded. Along [B], where the zags zig, you can comfortably fold the surface without introducing any new folds. The corrugation no longer provides a resistance. Folding it here will, however, further condense the height of the surface, as the angles intersecting with [B] give up some of their height for depth.

Along the line of [C], the surface will not fold—just as it couldn’t at [A]; but if the entire

region of [C] is turned into a gradually curving corner, that region will behave just as the zig-zag at [B] does (in fact it is a blown-up version of it), and then the height will likewise shrink.

Folding along [D], however, will not affect the height of the surface at all: that’s because the curves meet [D] at a

tangent, so they don’t interfere with it. (However, as the material to the left and right of D condenses, it will force D to bend along the point of contact.)

So here you have one difference between curved and straight-segment folding: the non-interference of tangential folds. And this principle happens to affect nearly everything about the possibilities of folding surfaces that have curved folds on them.

This is not a religious insight, or even a profound or novel mathematical one. But it might give a few people who are thinking now about sculpting in paper curves----a certain repose.