Origami, like anything with a long history, also has a destiny; by which I mean for instance that folds that were thought to be extremely difficult 100 years ago are child’s play today, and forms that 60 or 70 years ago were thought to be impossible without making cuts—so that a cut here & there was overlooked—are known as perfectly possible today with a little extra effort. Cuts accordingly are more strictly shunned even by non-puritans. The preference for the square has grown firmer, though it’s by no means absolute; and the field has grown enough to allow modulars, multi-part assemblages, though this is frowned upon in animal design (unless the units are sufficiently small to make it an extension of modular origami.) In short, the field has naturally pushed toward a set of ideals or strictures, which on approach have sometimes further split into other ideals and strictures each of which defines a new sub-field. Moreover, one can claim that this ‘destiny’ was present if dimly felt by some practitioners in earlier stages of development, and the very refinement and purification of such standards is part of what drove those pioneers forward.

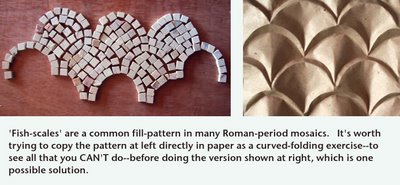

Curved folding, a subspecies of origami, has not been systematically explored by anything like as many people. (I’d say less than twenty people in the world; maybe less than ten, compared to several hundred systematic explorers with origami.) But I insist that curved folding too has a destiny---and I’ll tell you what it is. If in origami you rule out (or minimize) cutting, painting and gluing, in curvigami you also rule out folding itself. That is: hard folds and straight lines are viewed as necessary evils, acceptable in extremis, in just the way cuts were regarded in the origami of two or three generations ago.

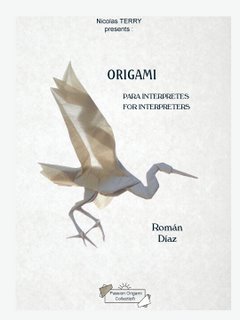

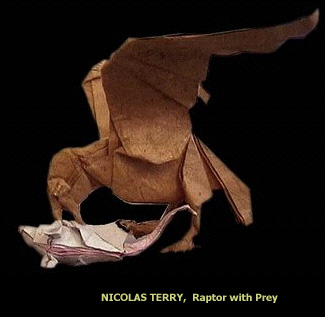

What about the square—another purist ideal that’s been refined (I mean increasingly insisted upon) over the generations? Here there is a more profound difference from straight-line and flat folding. Curvigami deals with surfaces and starts from the interior of the sheet, asking how you can manipulate that interior and what to do with the consequences of this manipulation for the rest of the sheet. This is unlike origami, which deals with edges, or the turning of surface regions into things that have edges, i.e., flaps. With curved folding you are dropped straight into the sea, where what you make are these ripples or waves; there is no shoreline you can depend on, and no “landmarks” either (I can go on some ways with this metaphor). So that the square with its edges and its whole language of 22.5 degree or 30 degree angles really becomes irrelevant. If you’re manipulating the edges and the corners of a square you are still more in origami mode than in curvigami mode.(Though this can be done masterfully too: witness Roman Diaz’ superb Tiger’s Head). I feel regrets about the loss of the square, truly I do, but it must go.

That being said, I can’t quite account for the residual attachment to the rectangle in my own curved folding, and to the right angle at its four corners. –Maybe it’s that one wants to keep it clear that a sheet, and a paper sheet, is the material of origin here, and sheets are rectangular by manufacturing tradition. Or maybe it’s that representation-surfaces in general—for instance paintings, and then movie and TV screens and now computer and cellphone screens—have historically allowed only very occasional lapses into other shapes: ovals, triangles, pentagons etc. It is the rectangle that silently screams today ‘surface’—or ‘surface without shape’, or ‘never mind about the edges or proportions, which within limits we can vary, it’s the interior content that counts’. That ‘surface condition’ exists also for surfaces to be made into curved-folds. A square, or any other regular polygon, draws far too much attention to its own outline and geometry.

Since curved folding is about surfaces, layers, too—the staple and mainstay of origami—also are downgraded. Layers are not mined as in origami for the creation of different entities (usually flaps); instead, multiple layers (which are avoided or minimized to begin with) are often treated as thicker versions of a single layer, and are folded all together.

To me, the great still-unanswered question is what the area of contact is between flat folding and curved folding. You might think, that since curved folding deals with surfaces, you can use curves for placing a surface ornamentation on an elaborate form, in, say, the way Robert Lang does famously with his Koi. But if the curves are put in first they prevent most subsequent manipulation of the familiar kind, so such an elaborate form is ruled out. Nor is it usually easy to put curves in after the fact, unless there is free material that reaches all the way to the cut edge. Roman Diaz’ Tiger’s Head (looks like I’ll have to write a separate essay on this model alone) introduces a few ornamental curves on the ‘leftover’ flat regions as a final step. This is not QUITE an afterthought, what it feels like instead is pedagogy: we’re being taught something about sculptural folding, in the rest of the piece, and here is an important aspect of sculpting that we don’t want to omit or the lesson won’t be complete. Nevertheless, the curves were not strictly necessary, some straight open crimps could almost have served. And the curves would not really have been possible, if the cut edge had not been free. --In some of my own things (e.g. Ernestine [yes, it's time for some new examples]), the ‘combination’ of curving/sculpted regions with flat/origami ones is given as a sort of ‘tease’, with the single-layer-curved head blending into the face (which has a few origami manipulations, I mean layers and flaps) and that in turn blending into the neck and chest, which is even more oriented to the language of straight-line origami. The suggestion--meant as usual to irritate certain people--is that the curves and the sculpting are the main thing, with the flat and straight origami being subservient to it, the raw material that it grows out of, in the way a polished marble sculpture can emerge from unthinking chiseled stone. Something similar about the relationship was suggested more humorously in ‘The Origami Eater’. But I haven’t given up the idea of curves as ornaments either; that’s part of what I was looking at in those ‘jars’, where a curve-pattern is carried around an edge; the n-sided jar-shape being the origami superstructure which supports the curving bas-relief ornament. Here the curved/sculpted regions and the geometric/origami regions are felt to be on more of an equal footing.

Why this fight over primacy, subservience etc? Must the elements of one language always be reduced to those of another? Can’t we all get along?

But looks like I’ve run out of space, or is it time. Let's leave this question open--for the time being.

[Added later: A slightly more formal discussion of curve-folding issues appears in the next article, "Lessons from Masters".]