I won’t say this is my favorite model. They are all my favorites while I am working on them. But this Horse--I have been with her the longest, starting I think in 1993. Also I have a set of ideals, almost an ideology, for animal origami design, and this is the model that comes closest to embodying it.

1. It is from a square

2. It uses clean angle divisions (15, 22.5) for all major folds (and most minor ones)

3. The preferred angle basis is 15 degrees (which I happen to like)

4. It uses strict referencing till very late in the sequence

5. The referencing is not artificial, but natural (= few/no extra steps just to make references)

6. The number of folds, given what you get at the end, is small (about 40 for the basic, standing version)

7. For horses in its class, paper usage is highly efficient

8. A quite reasonable model is produced with no post-folding, but material enough is there so that an accomplished folder can sculpt it to his heart’s content

9. Different poses or expressions are possible, because many long limbs are independently repositionable without affecting the others (head, neck, mane, tail, legs to a small extent)

10. It is from a Base or ‘embryo’ that can be readily modified to yield other animals

11. No body lines appear on the model that aren’t there in reality, and all those on the real animal are on the model

12. It is closed-back

13. Long limbs are visually continued by body lines

14. It is a beautiful animal.

Shortcomings too may be listed:

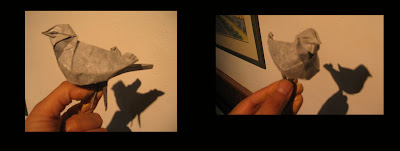

1. It is mainly a ‘flat’ model, though it becomes three-dimensional fairly naturally owing to paper thicknesses. (Unlike, e.g., the Pigeons from earlier this month, which are 3D directly by the folds.)

2. Legs should be longer still, to allow proper hooves and more motion poses.

3. While it is ‘closed-backed’, it is ‘open-headed’

4. If done with duo-toned paper, the head comes out a different color, as do the inner sides of the legs. This may or may not be desirable.

As if to balance out these deficiencies: unexpectedly, a version can readily be made that is also an Action Model.

DESIGN HISTORY. Of the three poses shown, the Galloping variation is most recent and has been through only 2 revision cycles (a few evenings’ work) so can’t be called perfect even if it’s good enough to show . The Grazing pose is much older & has been through 3 or 4 revision cycles, the first of them very long ago; I’m not fully satisfied with it either. But the Standing pose, the oldest, has been through at least 7 cycles, beginning I believe in 1993, then set aside till 2004 when I came back to origami. (During which time standards had toughened--for instance ‘open-backed’ animals like this horse used to be suddenly had become 'inferior'). At this point I’m not sure I can improve on this model any further, but you never know.

TRIPARTATE DIVISIONS. The length of the side of the square is divided into three, and so are the main 90-degree angles. The first—the length-division—is pretty much arbitrary; you can vary it and still get a decent animal only it will have a somewhat longer or shorter body which may not be suitable for a horse. (In fact a more perfect Horse can be made with a slightly different division, but I can’t be bothered to establish a reference of "side x 0.31".) The division of the angle into three is more fundamental; for clean folding purposes your options are either 15 or 22.5 degrees, and I happen to like multiples of 15. --Among other reasons because it was less common in 1993 when I started, though it is famously used in David Brill’s fine Horse from an equilateral triangle.

NATURAL FOLDS. A fold sequence can use strict referencing, or it can use ‘judgment calls’ or bizarre fractions for references. The designer most famous for strict referencing is the wonderful Komatsu, and he is liable to devote a fifth or more of the steps in a sequence to establishing marks precisely on the square. (He too has a Horse, of course, and a noble beast it is.) This calls attention to the act of referencing, which is in part why Komatsu has the reputation he has; but it seems to me that a higher & tougher design ideal is to establish references without special moves dedicated to them, that is, to make active, form-creating moves and base each next move on references naturally left by previous ones. Referencing is then no less strict for all that it happens silently.

EMBRYO. I worked hardest here to develop a supple animal base, or what might be called an ‘embryo’, which can be turned into a Horse or into any number of different animals. (It really is like embryology: remember Von Baer’s Law, that organisms are more like each other the younger the stage you look at them, both within and across species.) I prefer to get to an embryo stage much sooner than some other designers do, because this speed is what gives you the flexibility to change poses (or species) if need be.

SCULPTING. I'm a reasonably good sculptor and will often tinker for hours with a ‘finished’ model to get it into the right pose or expression. As a model designer this theoretically puts me in conflict with those folders who want a model at the end of a fold-sequence to come out as close to finished as possible, with little or no post-folding. Actually the conflict is less than it might seem--and enters at a different location than may be thought. Like everyone else, I want a model to be as good as it possibly can be straight off the assembly line. But I also try to design in as much flexibility as possible, so that if tinkerers like me DO want to change things at the end, they will not be locked in by the structure of the model. Designing for maximum uniformity of result is a very interesting concept, but there is also such a thing as designing for maximum variability, and it is not necessarily less challenging.

CREASE PATTERN. Someone who never folds from crease patterns really has no business unleashing on the world a CP of any model of more than minimal complexity. Understanding and skill is needed, to know what to include & exclude. Nevertheless—I promised, so here it is. --A holiday gift: to you who like such things.

Added Dec. 2010: Diagrams for the standing & grazing poses now available in my book, "Sculptural Origami".